Where Two Worlds Meet | The Coastlines of the Cape Peninsula

Article and Photography by Callum Evans

The coastline of the South Western Cape in South Africa is very special because it’s where two incredibly biodiverse habitats meet: the fynbos biome on the land and the kelp forests in the ocean. At the intertidal zone, the line between land and sea becomes blurred and animals can exploit a range of opportunities that would otherwise be unavailable to them.

The mountains of the Table Mountain National Park form part of the Cape Floral Kingdom (the fynbos biome), the smallest and richest of the world's plant kingdoms. Within the National Park alone, there are almost 2500 species of plant, many of which are found nowhere else in the world. Despite the intensive development of large areas of the coastline along the Cape Peninsula, there are still places where the fynbos grows all the way down to the coast. The plants growing closest to the shoreline form a thin belt of coastal vegetation known as the strandveld.

Here, plants have to adapt to nutrient-poor and loose soils. Low growing shrubs and succulents are dominant types of plants that grow within this habitat type and these plants help to stabilise the sand dunes along the coastline.

The Cape Point section of the Table Mountain National Park holds some of the most intact areas of fynbos on the Cape Peninsula and here the transition from montane fynbos to coastal strandveld is clearly visible. Within this part of the reserve are also large herds of bontebok and eland, as well as smaller numbers of ostriches, cape grysbok, red hartebeest and Cape mountain zebra. These herbivores are often seen feeding on the coastal vegetation and they can also get vital salts that are lacking in their diet from feeding on vegetation that grows in close proximity to the ocean and hence gets covered in spray from the waves.

Many animals visit the intertidal zone to take advantage of the resources that can be found in the rock pools or washed up on the shore. Birds like kelp gulls and sacred ibis scavenge on what gets washed up on the shore while cormorants and terns rest on the rocks in between fishing trips. Grey herons, ruddy turnstones, whimbrels and plovers hunt for food in the rock pools and in turn, the smaller birds are targeted by peregrine falcons. The endangered African black oystercatcher nests on undisturbed beaches and relies on the intertidal zone for the shellfish it feeds on. The African penguin, another iconic coastal-bird, often nests on offshore islands but at Boulders Beach (and Stony Point) they gather on the beaches above the high water mark and in the coastal vegetation to build their nests and raise their chicks.

Several troops of chacma baboons living on the Cape Peninsula are the only primates in Africa that visit areas of coastline to feed on shellfish and other marine organisms. They can often be seen at beaches in Cape Point Reserve feeding on mussels, limpets and even shark eggs. This provides them with vital sources of nutrients and proteins that would otherwise be lacking in their diet. This behaviour is passed down within the troops through the generations and has to be learned, as a number of the food items take a certain amount of skill and knowledge to find and collect. Limpets, for example, require baboons to use their large canine teeth to pry them off the rocks, and shark eggs can only be collected on the lowest of tides at specific times of the year.

Another mammal has to take to the ocean to find a lot of its food, but has to return to the land too. The cape clawless otters that live along the Cape Peninsula do much of their hunting in the shallow waters just off the coast, searching for crabs, fish and shysharks among the rockpools and kelp forests, returning to shore to eat their catch and rest. They are most active during the early hours of the morning and are traditionally one of the most elusive animals that inhabit South Africa’s coasts. Yet there are several individuals on the Peninsula that have become habituated in recent years, offering people a rare chance to see these endearing animals up close.

Larger animals like cape fur seals and occasionally southern elephant seals also use the coasts here to rest or sometimes to breed. Fur seals usually breed on offshore islands around Cape Town but in other parts of South Africa, like Robberg and the Namaqualand region, they do breed on the mainland.

Rockpools, created by the tides, are a dominant feature of the intertidal zone and can be full of life. Some can be less than 30 centimetres wide, while others can be 20-30 metres wide and almost 2 metres deep. As mentioned above, they provide hunting opportunities for numerous land animals while providing a home and shelter for a wide range of marine animals. Cape sea urchins carpet the rocks at the bottom of many pools, while anemones will often be nestled in cracks in the rock. Spiny and cushion stars, a variety of snails, crabs, klipvis, gobies, limpets and mussels are all typical rock pool inhabitants.

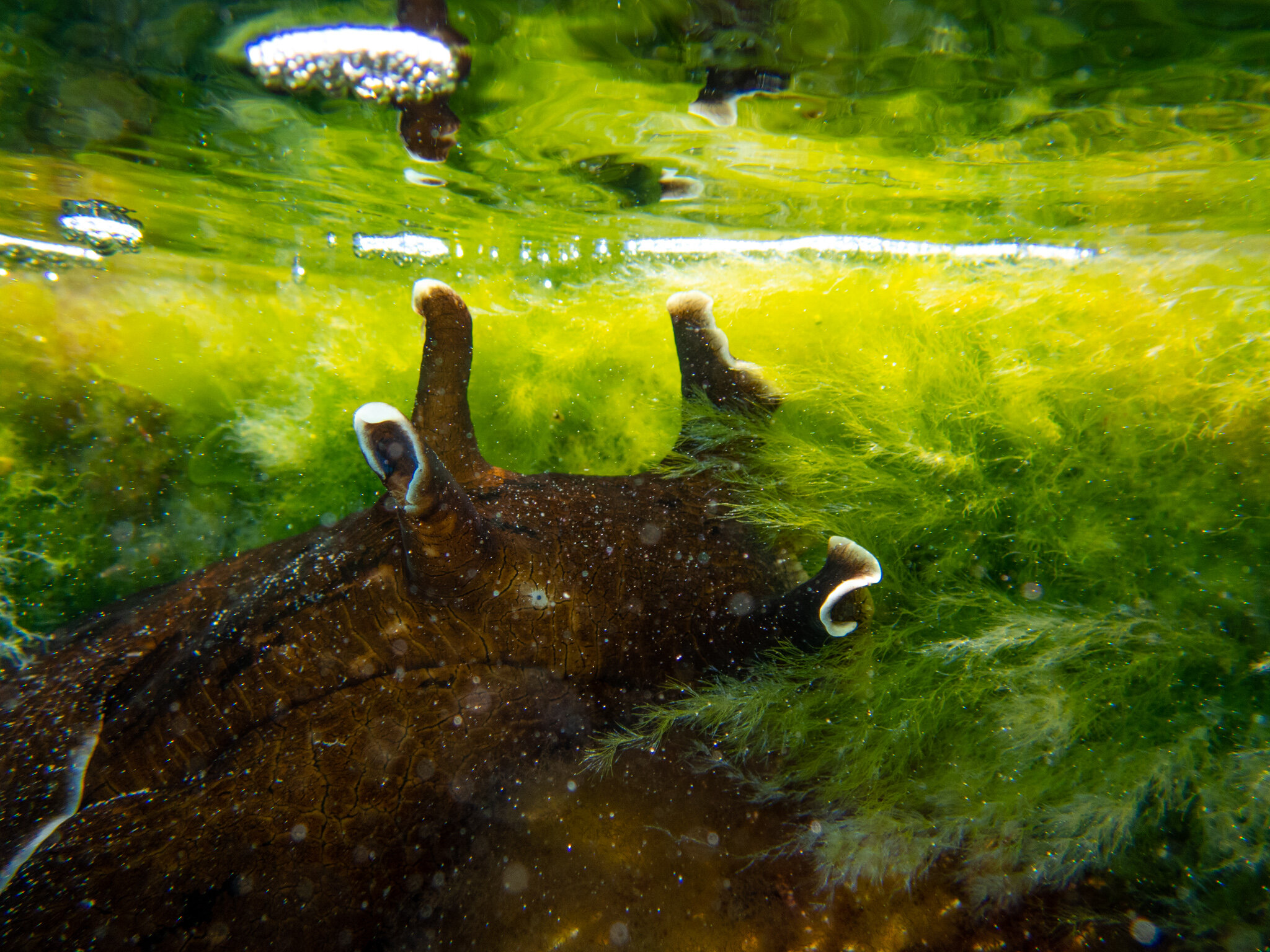

In large pools, there is a good chance of finding an octopus on the hunt. They are one of the few animals which can leave the water and move between the pools and the ocean. This is a crucial advantage in this ever-changing environment where pools could evaporate on the low tide or become too oxygen-depleted. The larger the pool (and the closer to the ocean it is), the greater the diversity of life it can support will generally be. Some hold soft corals, feather-duster worms, tubeworms, sea fans, nudibranchs, sea hares and prawns. I’ve even seen dark shysharks in tidal pools before, which for rockpools are very large predators indeed (despite the fact that the biggest was less than half a metre).

While the biodiversity along Cape Town’s coastlines is still very high, today there is limited space for it to occur. The rapid urbanisation of the areas surrounding the City of Cape Town has eaten away at vast areas of lowland fynbos and the demand for beachfront properties has taken up significant sections of coastline and threatens to destabilise these areas. Even on the more secluded beaches, plastic, netting, polystyrene and other items of trash can be found washed up, only a tiny percentage of what humans have thrown away into the oceans.

Our coastlines are crucially important ecosystems for many species and provide millions of people with food as well as recreational areas. In Cape Town, this transition zone between habitats has an essential part to play in our future. We must be far more vigilant and aware of how we interact with our coastlines.

Article and Photography by OCL Storyteller Callum Evans

Callum Evans | Photographer | Freediver | South Africa

Instagram - @callumswildlifephotography